Rescuing Providence: Prologue, a Book by Michael Morse

Monday, March 21, 2016

The chapter that GoLocal ran last week was part of the second book and was run in error.

I always thought that a day in the life of a Providence Firefighter assigned to the EMS division would make a great book. One day I decided to take notes. I used one of those little yellow Post it note pads and scribbled away for four days. The books Rescuing Providence and Rescue 1 Responding are the result of those early nearly indecipherable thoughts.

I’m glad I took the time to document what happens during a typical tour on an advanced life support rig in Rhode Island’s capitol city. Looking back, I can hardly believe I lived it. But I did, and now you can too. Many thanks to GoLocalProv.com for publishing the chapters of my books on a weekly basis from now until they are through. I hope that people come away from the experience with a better understanding of what their first responders do, who they are and how we do our best to hold it all together,

GET THE LATEST BREAKING NEWS HERE -- SIGN UP FOR GOLOCAL FREE DAILY EBLASTEnjoy the ride, and stay safe!

Captain Michael Morse (ret.)

Providence Fire Department

The book is available at local bookstores and can be found HERE.

PROLOGUE

0230 HOURS

“Rescue 1, are you available?”

“Roger, what have you got?”

“Respond to Providence College for a student who has fallen off of a roof.”

“Rescue 1, on the way.”

We are worn out, finishing a 38. Lori hits the lights and siren and changes direction, driving toward the incident.

It only takes a minute to get there. The campus is quiet; most of the kids are asleep or cramming for finals. Lifeless soccer fields and empty administration buildings and classrooms lead us toward the brick, seven-story dormitory.

Twenty-five years ago 10 girls jumped to their deaths from one of the dorms here, trying to escape a fire that started when some party decorations lining the walls ignited. They couldn’t wait for the ladders that would have rescued them, the flames too hot and smoke too thick. Some crashed to the ground in front of their rescuers, seconds away from salvation. It was the worst day in the history of the Providence Fire Department. We have had more than our share of bad days.

A security guard directs us up a hill to the base of St. Joseph’s Hall. Another guard has a student in his grasp, the latter’s anguish evident as he weakly fights to get free, his guttural wails echoing off the buildings.

At the top of the hill and the base of the building, lying in a crumbled heap, is our victim. I get out of the rescue and walk closer, hoping beyond hope that this is some bizarre prank. It isn’t.

I am a firefighter. People look to me when they need help. The crumbled heap is a kid named John. He looks at me through eyes that have popped from their sockets yet miraculously still focus on my own. He tries to speak; blood and teeth flow from his mouth rather than words.

“It’s bad,” I say to Lori as she wheels the stretcher close. With help from Engine 12, who has been called to assist, we immobilize our patient and then load him into the truck and head for the trauma room at Rhode Island Hospital, the area’s only Level 1 trauma center. John fights for life all the way. His broken bones are hinged in multiple places; as he moves his shoulders and hips, the limbs go in opposite directions. The hat he wears, a light brown wool cap with earflaps that can be tied, finally falls from his head onto the blood-splattered floor of the rescue. I remember hats like that from my childhood, when mothers and grandmothers would bundle their kids up before sending them into the cold.

The hats have regained their popularity with older kids. It’s funny how things come and go, I think. I pick up the hat and place it on his chest, the only part of his body that doesn’t appear outwardly broken. Inside, his vital organs are a scrambled mess. He somehow gathers the strength to grasp my wrist as I try to keep him from moving.

I am amazed both by the power still exuding from his broken body and the emotional response his desperate gesture has on me.

The mangled mass of flesh and bone become more to me than I had intended, my quest to distance myself from the emotional carnage that lies ahead destroyed. His grip on my arm goes directly to my heart, breaking now that we have become more intimate. I wonder to myself, who am I to be present and in charge as this drama unfolds? I’m just a regular guy who a few years ago couldn’t manage his own life, never mind leading a team of firefighters in this grim effort.

I put aside my self-doubt and march on—there’s no time for indecision when a life hangs in the balance. The responsibility is sometimes overwhelming, but worrying about it doesn’t help anybody.

I’m certain that the look on the faces of Lori and the guys from Engine 12 mirrors my own. I see horror and pity mixed with revulsion in their expressions as we work. We do all we can: start IVs, give oxygen, and try to comfort our patient while we endure what for some of us is the longest ride of our careers.

An hour after we have handed what is left of John over to the emergency room staff, I sit on the floor outside the trauma room,state report on my knees, the empty spaces waiting to be filled.

My hand holds a pen that I can’t get going. The guys from Engine 12 are in the barn waiting for the next alarm. Lori is with the triage nurses, who are busy with the kid who witnessed his best friend fall 80 feet from the slippery dorm roof.

According to John’s friend, the boys had finished cramming for their exams and were sneaking onto the roof for a smoke. A window in a janitor’s closet provided access to the roof. This wasn’t the first time the window has been used for access. A beautiful view of the city awaits those daring enough to make the trip. The first boy made it onto the roof and then waited for John. Something happened—John slipped and started sliding down the roof toward the edge. It happened fast. John’s friend watched him go over, and then he somehow made it back through the window, out of the closet, down the stairs to the first floor, and out the front door to see if he could help. He was the first to see the result of an 80-foot fall onto frozen ground. John was critically injured, and his friend’s life was forever changed by what he saw. (I can only hope he gets the help he needs and doesn’t push his feelings away as guys his age are prone to do.)

From the corner of my eye, a priest appears at the end of the long corridor we call “trauma alley.” The hospital’s six trauma rooms line the narrow hallway, filled with the most advanced med ical equipment available. At a moment’s notice these rooms can be filled with trauma teams consisting of doctors, nurses, respiratory experts, and support staff. Now, most are empty. One of the rooms shows signs of activity, a lone janitor mopping buckets of blood from the floor. John has been taken upstairs to surgery.

Two people join the priest, and they make their way toward me under the bright fluorescent lights up trauma alley. They are my age, dressed in sweatshirts and sweatpants, things found at a moment’s notice, but no coats. They cling to each other, the man holding the woman up, supporting her as they make the long walk toward an uncertain future that seemed so bright when they fell asleep hours before. Now it is shrouded with uncertainty and fear. I know why they are here and the bad news that awaits them. Hoping beyond hope that everything will be as it had been, they struggle past me. I cowardly look down at my empty report and pretend to write, not wanting to see up-close the effects of this tragedy any more this night.

They are a close, religious family from a nearby Massachusetts town: Mom, Dad, and three kids. They sent their son to a Catholic college hoping he would be safe. They walk past, not knowing that I am the one who peeled their son off the curb at the bottom of his dorm and held him together through the ride to the hospital. I know he would have died on the pavement if not for our intervention, and I get some satisfaction from knowing his parents would have the opportunity to hold their child once more while life still flows through his veins. Whether that will be enough in the hard years to come, I will never know. I don’t think he will make it much longer.

Somehow I finish the report, help Lori clean the rescue vehicle, and limp back to the station. All is quiet there. The engine and ladder companies don’t turn a wheel all night. In my office a stack of reports waits to be logged into the computer. After thirteen runs, I have three hours to go. I haven’t slept in days; I am exhausted, depressed, and dirty. Too tired to shower or log the reports into the computer system, I collapse onto my bunk. Mercifully, I sleep until my relief wakes me at seven.

After an hour of doing reports, I am on my way home. I turn on the radio, hoping to hear some music and clear my head. It is the top of the hour, and my favorite station does a five-minute news segment at this time on weekdays. The story of the student who fell from the seventh floor of his dorm leads the news. He is reportedly still in critical condition. I listen to the details, amazed at how cold and generic the information sounds when recounted by somebody who is just reading the news. My mind is still full of every minute detail—the smell of blood mixed with diesel fumes from the truck’s exhaust, similar to charred meat cooking on a propane grill; the tension of the rescuers; the horror of the wit -nesses; and the victim’s pain all mixed together, forming a cloud of desperation that can be felt only by those who have been there. You could tell the story a hundred times and the people hearing it will never feel that desperation, can never appreciate what really went on. Only those unfortunate souls who have lived through such experiences bear the full weight of the memories.

Michael Morse lives in Warwick, RI with his wife, Cheryl, two Maine Coon cats, Lunabelle and Victoria Mae and Mr. Wilson, their dog. Daughters Danielle and Brittany and their families live nearby. Michael spent twenty-three years working in Providence, (RI) as a firefighter/EMT before retiring in 2013 as Captain, Rescue Co. 5. His books, Rescuing Providence, Rescue 1 Responding, Mr. Wilson Makes it Home and his latest, City Life offer a poignant glimpse into one person’s journey through life, work and hope for the future. Morse was awarded the prestigious Macoll-Johnson Fellowship from The Rhode Island Foundation.

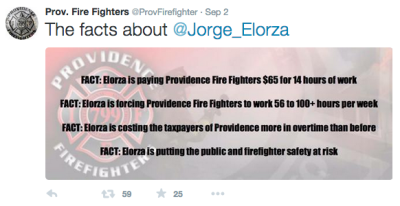

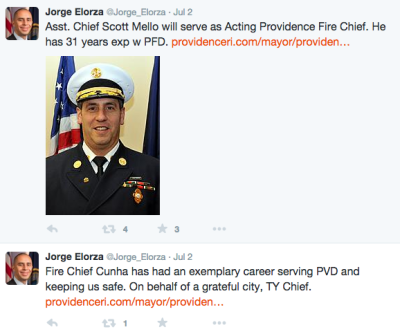

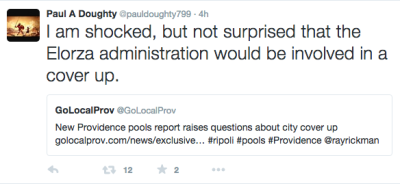

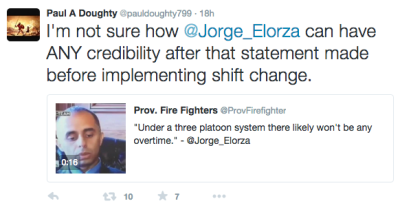

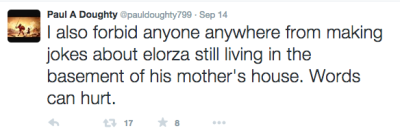

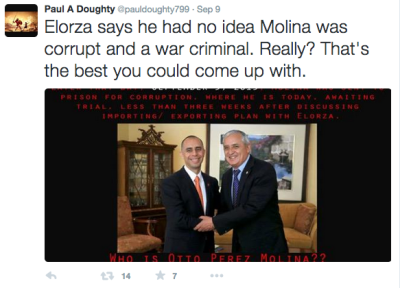

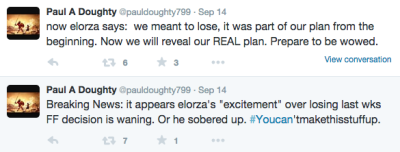

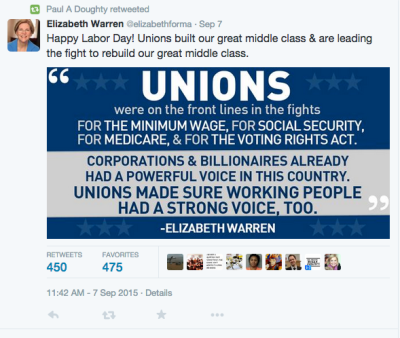

Related Slideshow: Providence Firefighter Tweets

Related Articles

- Starting Next Week: GoLocalProv Starts Publishing “Rescuing Providence” By Michael Morse

- Johnston, North Providence Firefighters To Square Off in Football Game

- NEW: Providence Fire Fighters Endorse Taveras for Governor

- NEW: Massive Providence Fire Took Place at Marijuana Producers Association Building

- GoLocalTV: Providence Firefighters Oppose Elorza’s Shift Plan

- 63 Providence Firefighters Made More Than 100K in FY 2014

- E-Mail Blasts Providence Fire Contract

- Providence Fire Bosses - $700,000 in ‘Illegal’ Severance Pay

- Providence Firefighter Pensions—Disability vs. Regular

- NEW: Providence Firefighters Asked to Take Pay Cuts

- GoLocalProv Uncovers: Providence Fire Bosses File to Unionize

- Providence Firefighters’ Raise Could Trigger Millions in Raises for Teachers

- Providence Firefighters to Hold Rally Against Elorza

- EDITORIAL: Kudos to Providence Firefighters

- Providence Firefighter Union Criticizes City for Not Appointing Fire Chief

- Providence Fire Department - Total Confusion About Who’s in Charge

- Providence Firefighters Criticize Administration at Miguel Luna Remembrance

- NEW: At Least 14 Providence Firefighters to Retire in January

- Providence Fire Department in Chaos

- Suspect Wanted in Hit and Run Involving Off-Duty Providence Firefighter

- BREAKING: Providence Firefighters Score Court Victory Against Elorza’s Staffing Plan

- Is Providence Firefighters’ Social Media Campaign Beating Elorza?

- Providence Firefighters to Hold Listening Tour Throughout City

- NEW: Arson Fire at Pearl Restaurant to be Investigated by Providence Fire Dept, ATF

- Council Members Blast Providence Fire Captain’s Dismissal